- Home

- »

- Germany

- »

- Berlin

- »

- Museum Island

- »

- The Berlin Egyptian Museum

- »

- The Berlin Egyptian Museum - The Story of the Egyptian Museum

The Story of the Egyptian Museum

The History of the Egyptian Museum

Egypt! Perhaps no other culture in the history of mankind casts quite the same spell over us, with its ancient myths, its pharaohs and pyramids, mummies and the riddle of the hieroglyphics.

Berlin’s Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection constitute one of the most significant Egyptology collections in the world. The countless treasures it contains give us an unmatched opportunity to immerse ourselves in the mystery of one of humankind’s oldest civilizations. Last, but not least, the Egyptian Museum is home to perhaps Berlin’s best known work of art – and one of the most beautiful pieces of Egyptian art yet to be unearthed: the bust of Nefertiti.

At the beginning of the 19th century, ancient Egypt was far from being an obvious object of interest to serious European scholars. For centuries, Egyptian culture had been dismissed as prehistoric and its art as primitive. It was mostly treasure hunters or adventurers who roamed Egypt.

Ironically, the birth of Egyptology as a science owes much to a well-known adveturer. In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte tried to conquer Egypt. His military campaign failed, yet it had lasting consequences: in its wake, researchers took up the scientific study of ancient Egyptian civilization. All of Europe was fascinated with the new discoveries coming to light. And Berlin was no exception. But as would so often be the case over the course of the museum’s history, it was not officialdom that realized the vast project, but rather the passion of a single individual.

Joachim Selim Karig, Chief Curator of the museum from 1963-1995:

“The beginnings of the Egyptian Museum can be traced back to a private individual. Although he worked at court, he collected artefacts at his own expense and on his own time. His name was Heinrich von Minutoli. He was tutor to Prince Charles of Prussia. After he left that post, he travelled to Egypt and put together quite an impressive collection.”

The king did, however, provide a few scientists to accompany Minutoli on his journey. But Minutoli’s travel plans proved too much for them. An unplanned stop in Trieste – where Minutoli married, taking his new bride along on the rest of the trip – upset the learned scholars. By the time they arrived in Egypt, the group was hopelessly at loggerheads.

Those disagreements, and his fight for recognition, would continue to dog the whole of Heinrich von Minutoli’s life. A former soldier and ardent devotee of all things Egyptian simply didn’t fit in to the dry, Protestant world of Berlin academia.

Joachim Selim Karig:

“I wouldn’t want to say that he was a strange character, but there was definitely a bit of the adventurer in him. He certainly wasn’t the type you would imagine a Prussian civil servant to be.”

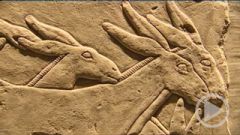

But Minutoli’s achievements speak for themselves. He split from the group of academics and continued to the Nile Valley on his own. His enormous physical and financial commitment was rewarded. He discovered the entrance to the step pyramid built for King Djoser at Saqqarah. But what he did, above all, was collect precious antiquities by the camel load. This statue of Ahmes Nefertari, for example, remains even today one of the highlights of the museum’s collection.

Minutoli travelled back to Berlin carrying about 3,000 artefacts. But that was only a small portion of his collection. Most of it was sent back to Europe by sea. The shipment contained hundreds of statues and stelae and a sarcophagus weighing a ton or more. Unfortunately the Danish vessel “Gottfried” was only designed for coastal duty. Already weakened from the stresses of the journey, and completely overloaded, she was no match for a severe storm that struck on March 12, 1822. Off Cuxhaven at the mouth of the Elbe River, just short of her destination, the “Gottfried” capsized and sank, taking her precious cargo to the bottom of the sea.

The Egyptian Museum suffered its first great disaster before it had even opened. To this day, egyptologists still refuse to accept the loss.

Joachim Selim Karig:

“... Particularly the large sarcophagus made of granite, which weighs several tonnes. It won’t have floated off, it must still be there. We’re still hoping to find a sponsor to help us look for the collection and maybe recover it.”

But it was an Italian businessman who became the official founder of the Berlin museum. Giuseppe Passalacqua originally went to Egypt in 1820 to trade in Dongola horses. But fate had something else in store for him.

Hannelore Kischkewitz, researcher at the museum:

“Like many fans of Egypt, Passalacqua surfaced from the wave of Egyptomania of the time. He was no egyptologist, this science didn’t exist yet. Champollion’s marvellous discoveries still lay in the future. When Passalacqua went to Egypt, scientific egyptology was in its infancy. It’s astounding what he was able to find out considering he had no real knowledge of egyptology.”

Passalacqua threw all his energy into the new task. The former horse trader became a passionate collector and authority on the subject. But it was above all his habit of meticulous documentation that continues to provide valuable information to egyptologists, even today. The treasures he brought back also enriched the museum, for instance, this Ptah family group. After many years and after mounting several astoundingly circumspect excavations, Passalacqua exhibited his collection of treasures in 1826 in Paris. The exhibition was an international success, and the Prussian king made a special trip to see it. He was so enthusiastic that, following the advice of the explorer Alexander von Humboldt, he bought the entire collection. Passalacqua was paid 100,000 francs and given a contract to set up his exhibition in Berlin.

Which is how Berlin’s Egyptian Museum first saw the light of day, on July 1, 1828 in the winter garden of Monbijou Palace. And Passalacqua “went native” in the Prussian capital: the former adventurer and layman was appointed lifetime director of the museum.

But the post wasn’t to bring him unalloyed happiness. In 1833, the Berlin academy sent a young philologist by the name of Richard Lepsius to Paris. He was tasked with familiarizing himself with the still-new field of research into ancient Egypt. Something he did with enormous success.

Dietrich Wildung, Director of the museum from 1989-2009:

“About 10 years after Champollion’s work on deciphering hieroglyphics started in Paris in 1822, Lepsius completed it. The two of them – Lepsius and Champollion – are the fathers of Egyptology.”

Under the patronage of King Frederick William the Fourth, Lepsius led the “official Prussian expedition” to Egypt. On October 15, 1842 – the king’s birthday, he raised the Prussian flag at the top of the Great Pyramid at Giza. Evidence of the expedition’s triumphant success can be found today in the Berlin museum in – among other things – the jewellery of Queen Amanishakhete. The three years of Lepsius’ expedition opened a new dimension in egyptology, and more than 1,500 artefacts were added to the Berlin collection. Back in Berlin, the brilliant scientist expected a well-earned thank you. He became the first professor of egyptology ever, in 1850, but...

Hannelore Kischkewitz:

“Lepsius had been promised something that he would get the museum director job in Berlin after university. But Passalacqua had the post. And he kept it until 1865, when he died.”

Looking for a diplomatic solution, the powers that be made Richard Lepsius co-director of the museum in 1855. But diplomacy was not Lepsius’ strong suit.

Dietrich Wildung:

“Lepsius must have been a very dominant person who wouldn’t put up with rivals of equal status around him. That was clear during the time he was vice-director of the museum – from 1846 to 1864 – in his attitude toward the nominal director, Giuseppe Passalacqua, an amateur. And that attitude was even more extreme toward the brilliant Berlin egyptologist Heinrich Brugsch, who had published a demotic dictionary when he was still in secondary school. Lepsius did everything he could to make difficulties for him and try to hinder [the growth of] his international reputation.”

Although Giuseppe Passalacqua was the museum’s director for almost 40 years, not a single picture of him has survived. We’ll never know whether that’s due to pure historical coincidence or the influence of his adversary Lepsius.

Passalacqua also drew the short straw on what would be the museum’s largest project during his tenure. In 1841, art-lover King Frederick William the Fourth announced a magnificent plan to turn the entire northern end of an island in the Spree into a “sanctuary of art and science”. Thus, the idea of Museum Island was born. Both directors were charged with developing a concept for a new Egyptian museum. Richard Lepsius pushed through his ideas right down the line. Passalacqua’s designs were never even seriously considered, although seen in a modern light, they display great educational talent.

Passalacqua didn’t live to see the new museum open in 1866. Lepsius was put in charge of the museum, finally becoming its sole director after almost 20 years of waiting.

The transition from adventurers to scientists in the history of the Egyptian museum seemed to be completed with the 1884 appointment of Adolf Ermann as Lepsius’ successor. Ermann was a committed scientist, who was capable of achieving great things one step at a time. One milestone that was a result of his painstaking and detailed work was the great “dictionary of the Egyptian language”, which remains a basic reference work for every egyptologist today. The Berlin Academy of Sciences has since taken over the project of maintaining the dictionary. Berlin is also home to the central catalogue of all known papyruses in the world.

Adolf Ermann’s greatest achievements as director of the museum were based on the acquisition of art pieces, as opposed to archaeological digs. On his first visit to Egypt, for instance, he bought this exquisite Psamtik family grouping, a masterpiece of the late Egyptian period.

Just ten years later, he pulled off a spectacular coup. He bought the head of a statue from English collector who had won it gambling. The head, known as the “Berlin green head” is renowned worldwide as a fine example of Egyptian art.

But even during Ermann’s tenure, it was once again a man working in Egypt who was to have a greater influence on the museum than the director himself. His name was Ludwig Borchardt. Borchardt was above all a gifted archaeologist who had been working on digs in Abu Sir since 1895.

Years later, he would present the museum with one of its greatest scientific triumphs. Ermann laid the foundations for it in 1888, when he acquired a series of seemingly nondescript tablets covered in cuneiform writing. They turned out to be an archaeological sensation. They were part of the state archives of Tell el-Amarna, the seat of the legendary “heretic king” Akhenaten.

A race to the prize broke out, with England, France and Prussia all competing bitterly for permits to excavate the ruins at Amarna. Thanks to good connections with the Egyptian authorities, Borchardt emerged the victor. His finds at Amarna opened a new chapter in the history of egyptology. Working at Amarna in the winter of 1912, the archaeologists discovered the workshop of the pharaoh’s sculptor, Thutmose. On December 6th, shortly after lunch, the neck of a bust was uncovered in a corner. After endless minutes, Borchardt was holding in his hands one of the greatest masterpieces of ancient history – the bust of Nefertiti. In a letter, he wrote: “it’s no use describing it, you must see it!”.

Apart from the National Museum in Cairo, Berlin’s Egyptian Museum holds the most significant collection of antiquities from the Amarna period. But none of that would have been possible without a man who operated largely in the background.

Dietrich Wildung:

“James Simon was a businessman in Berlin; a very successful one. He financed the large digs of the Middle East Museum and the Egyptian Museum, in Mesopotamia and Egypt. He got the finds from Amarna. And in 1920, he gave them all to Berlin’s state museums as a gift.”

Thanks to Simon’s gift, the bust of Nefertiti went on display in the museum in 1924 and immediately became the museum’s main draw.

World War One marked the end of the great era of explorers and discoverers. There was little place for archaeological expeditions amid the turmoil of the 1920s. The museum in Berlin spent much of the following decades trying to protect the collection from destruction. World War Two was, of course, the greatest catastrophe. As early as 1939, the museum’s treasures were moved to air-raid shelters. But in the last days of the war, they were no longer safe even in the bunkers.

Werner Kaiser, Director of the Egyptian Museum in West-Berlin from 1960-67:

“In March 1945, as the fighting grew closer and the air raids more and more frequent, it was decided to move the objects to abandoned mines in other parts of Germany. But there was no time to sort out the most important objects and other things were taken there as well.”

Shortly before the end of the war, bombs hit Berlin’s New Museum. The north wing was completely destroyed and large portions of the building were gutted by fire. Countless museum pieces also fell victim to flames.

After the war, new excavations were started ... but this time in the heart of the German capital. Berlin was divided for decades. And the remnants of the Egyptian Collection were also torn between East and West.

A large portion of the art treasures was taken to the Soviet Union after the war. They were returned in 1958 and the East Berlin Egyptian Museum was re-opened in the Bode Museum. Things took a little longer in the West. The Americans and the British had taken part of the collection for safekeeping and returned it later to West Berlin. For many years, the bust of Nefertiti and selected works from the Amarna period were available for viewing only in three small rooms in the Dahlem museum. It was not until the 1960s that Werner Kaiser was given the task to set up a real museum in West Berlin.

Werner Kaiser:

“It started with about 250 crates that were brought from East Berlin to West Berlin right before the end of the war. They were returned to us in the 1950s and put in storage until the Stüler building gave us the opportunity to set up a museum. It took another three or four years before the building, was ready. During that time, we unpacked the crates and marvelled at what we found. We had very little idea what was in them.”

A divided city and two separate museums – once again, the museum’s fate was guided by the passion and extraordinary commitment of egyptologists.

Steffen Wenig, Curator at the museum (East Berlin) from 1959-1978:

“In addition to the losses in Berlin, there were losses elsewhere of course. We know that there was a lot of destruction in the Sophienhof Palace in Mecklenburg. One of the restorers went to Sophienhof and found among the gravels on the road pieces of bas-reliefs, fragments of stelae; he brought back the well-known Maya relief from Sophienhof. I don’t think we’ll ever have a complete idea of what was really destroyed. But we managed to get by after you, Joachim, joined the Western museum, by contacting each other, despite the wall.”

Joachim Selim Karig:

“We knew each other from before. We were both at great pains to clarify what remained. We didn’t have any documentation in West Berlin – no inventory, no card catalogue, nothing. We had the lists of things that had been stored; they were made at the destinations in West Germany. Using those, we were able to more or less identify the pieces, many of which were even missing their inventory numbers. You helped us by taking our provisional inventory cards, which at that time we could still send over here to the East, and comparing them to the inventory lists, adding to them. So over time, we gained an idea of what we had.”

It was not until 1991, one year after the German re-unification, that the separated collections of the Egyptian Museum were finally reunited: After nearly half a century, an exhibition joining the two halves of the collection were presented at the Charlottenburg museum. In summer 2005, the reunited collection was moved back to the Old Museum on Museum Island.

And in the fall of 2009, 70 years after the outbreak of World War II, the collection is finally coming full circle. At the same time, the re-opening of the New Museum constitutes the beginning of a new era. The legacy of Borchardt and Simon, Ermann and Lepsius, of Passalacqua and Minutoli is finally able to return to its old, yet completely new home.